Images

October 21, 2019 - A Very Dry Season

Tweet

In southern Africa, the dry season usually begins in late April or May, coming to an end when rains fall in November, bringing life-giving water and cooler temperatures to the region. The heaviest rains, which fall in the highlands of Angola in summer (January and February), slowly flow down the Okavango River to spread across the wide Okavango River Delta by June, creating an oasis in the midst of the dry season which supports agriculture, animal life, tourism and other human activity. The flow typically also fills Lake Ngami, southwest of the Delta, a shallow lake that has been designated an Important Bird Area by Birdlife International, at least in good years.

Good years are becoming harder to find in this region, however, thanks to persistent and sometimes unrelenting drought.

In October, 2018, the Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System (GDACS) reported an Orange Alert for drought for Southern Africa, including Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. That report predicted an extended, worsening drought over at least the next year. The drought has certainly persisted, but the situation was worse than expected. The longed-for rains barely materialized, proving erratic and limited. By September, the drought had deepened, creating severe food insecurity, and loss of livestock and wildlife. Even tourism was impacted, with the waters of Victoria Falls, touted as the world’s largest waterfall, carrying only about one-third of the normal flow.

In mid-September, a photojournalist, Martin Harvey, visited Lake Ngami. He documented the devastation of the nearly-dry lake: hippopotamus shoulder-to-shoulder in the last inches of muddy lake water; livestock stuck in deep mud as they frantically fought to find a drink; and people trying to catch the last of the catfish before they died in the drying lake. On October 9, the United Nations World Food Programme published a report that stated, “With temperatures rising at twice the global average and designated a climate “hotspot” by the intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Southern Africa has experienced normal rainfall in just one of the last five growing seasons.” A record 45 million people in the 16-nation South African Development Community (SADC) face severe food insecurity, with 9.2 million people experiencing “crisis” or “emergency” levels of food insecurity in eight Southern Africa countries. The report stated that in late 2018 and early 2019 many western and central areas experienced the driest growing season in a generation, precipitating widespread crop failure in Zimbabwe, northern Namibia and southern parts of Angola, Botswana and Zambia. The population in “crisis” or “emergency” status is likely to rise to 13 million early in 2020.

Competition for water and food has impacted the relationship between animals and humans. When driven by thirst, elephants have been reported attempting to break fencing to gain access to swimming pools. Some groups have tried to help by drilling boreholes, so that elephants could find water away from human settlements. But competition for limited resources has become a political issue, particularly in Botswana, where an elephant population of about 130,000 competes with a human population of just over 2 million. In May, President Mokgweetsi Masisi lifted a ban on the trophy hunting of elephants. He was quoted by The Independent as saying that, in his view, the numbers of elephants are now “far more than Botswana’s fragile environment, already stressed by drought and other effects of climate change, can safely accommodate,” leading to a “sharp increase” in conflict between humans and elephants. He hopes a limited, permit-oriented culling of elephant will help alleviate the crisis.

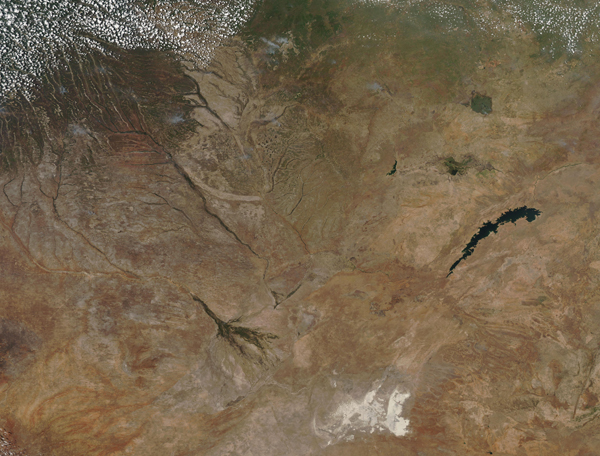

On October 18, 2019, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on board NASA’s Aqua satellite acquired a true-color image of part of Southern Africa including the counties of Angola, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Botswana.

The entire area appears washed in browns and tans, with only a few areas showing substantial green of vegetation. The highlands of Angola (upper left) are substantially green, with the course of several rivers also outlined in green. The Okavango River, which terminates in the fan-like Okavango River Delta shows little water in its banks or green along its banks. The Delta itself appears more like a few relatively stubby fingers rather that the normally broad fan-shape so iconic in satellite images of the region. Due south of the greenest part of the Delta, the comma-shaped Lake Ngami, typically filled with blue water, appears almost completely brown due to widespread mud (best seen in high resolution). The large white areas are the Makagadikgai Salt Pans, one of the largest salt pans in the world.

Image Facts

Satellite:

Aqua

Date Acquired: 10/18/2019

Resolutions:

1km (1.2 MB), 500m (3.6 MB), 250m (2.8 MB)

Bands Used: 1,4,3

Image Credit:

MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC

Tweet

In southern Africa, the dry season usually begins in late April or May, coming to an end when rains fall in November, bringing life-giving water and cooler temperatures to the region. The heaviest rains, which fall in the highlands of Angola in summer (January and February), slowly flow down the Okavango River to spread across the wide Okavango River Delta by June, creating an oasis in the midst of the dry season which supports agriculture, animal life, tourism and other human activity. The flow typically also fills Lake Ngami, southwest of the Delta, a shallow lake that has been designated an Important Bird Area by Birdlife International, at least in good years.

Good years are becoming harder to find in this region, however, thanks to persistent and sometimes unrelenting drought.

In October, 2018, the Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System (GDACS) reported an Orange Alert for drought for Southern Africa, including Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. That report predicted an extended, worsening drought over at least the next year. The drought has certainly persisted, but the situation was worse than expected. The longed-for rains barely materialized, proving erratic and limited. By September, the drought had deepened, creating severe food insecurity, and loss of livestock and wildlife. Even tourism was impacted, with the waters of Victoria Falls, touted as the world’s largest waterfall, carrying only about one-third of the normal flow.

In mid-September, a photojournalist, Martin Harvey, visited Lake Ngami. He documented the devastation of the nearly-dry lake: hippopotamus shoulder-to-shoulder in the last inches of muddy lake water; livestock stuck in deep mud as they frantically fought to find a drink; and people trying to catch the last of the catfish before they died in the drying lake. On October 9, the United Nations World Food Programme published a report that stated, “With temperatures rising at twice the global average and designated a climate “hotspot” by the intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Southern Africa has experienced normal rainfall in just one of the last five growing seasons.” A record 45 million people in the 16-nation South African Development Community (SADC) face severe food insecurity, with 9.2 million people experiencing “crisis” or “emergency” levels of food insecurity in eight Southern Africa countries. The report stated that in late 2018 and early 2019 many western and central areas experienced the driest growing season in a generation, precipitating widespread crop failure in Zimbabwe, northern Namibia and southern parts of Angola, Botswana and Zambia. The population in “crisis” or “emergency” status is likely to rise to 13 million early in 2020.

Competition for water and food has impacted the relationship between animals and humans. When driven by thirst, elephants have been reported attempting to break fencing to gain access to swimming pools. Some groups have tried to help by drilling boreholes, so that elephants could find water away from human settlements. But competition for limited resources has become a political issue, particularly in Botswana, where an elephant population of about 130,000 competes with a human population of just over 2 million. In May, President Mokgweetsi Masisi lifted a ban on the trophy hunting of elephants. He was quoted by The Independent as saying that, in his view, the numbers of elephants are now “far more than Botswana’s fragile environment, already stressed by drought and other effects of climate change, can safely accommodate,” leading to a “sharp increase” in conflict between humans and elephants. He hopes a limited, permit-oriented culling of elephant will help alleviate the crisis.

On October 18, 2019, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on board NASA’s Aqua satellite acquired a true-color image of part of Southern Africa including the counties of Angola, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Botswana.

The entire area appears washed in browns and tans, with only a few areas showing substantial green of vegetation. The highlands of Angola (upper left) are substantially green, with the course of several rivers also outlined in green. The Okavango River, which terminates in the fan-like Okavango River Delta shows little water in its banks or green along its banks. The Delta itself appears more like a few relatively stubby fingers rather that the normally broad fan-shape so iconic in satellite images of the region. Due south of the greenest part of the Delta, the comma-shaped Lake Ngami, typically filled with blue water, appears almost completely brown due to widespread mud (best seen in high resolution). The large white areas are the Makagadikgai Salt Pans, one of the largest salt pans in the world.

Image Facts

Satellite:

Aqua

Date Acquired: 10/18/2019

Resolutions:

1km (1.2 MB), 500m (3.6 MB), 250m (2.8 MB)

Bands Used: 1,4,3

Image Credit:

MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC