Images

December 19, 2022 - North Caspian Ice-up

Tweet

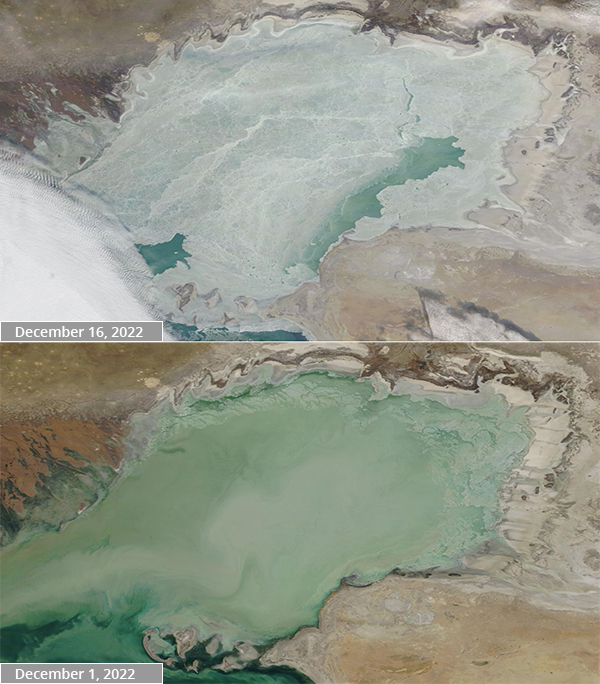

On December 16, 2022, winter ice-up of the North Caspian Sea was nearly completed, thanks to rapidly falling temperatures in the closing days of autumn.

This pair of true-color images captured by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on board NASA’s Terra satellite only fifteen days apart illustrates the fast-forming ice. The upper image, acquired on December 16, reveals the entire area almost entirely ice-covered, with only small windows of open water visible. The lower image, acquired on December 1, shows only a thin layer of ice floating near the white mineral-encrusted shoreline.

The Caspian Sea, with a total surface area spanning about 143,200 square miles (371,000 square kilometers), is considered to be Earth’s largest inland water body. There are three distinct sections of the Caspian Sea, and, despite cold, harsh winter temperatures across much of the region, only the extremely shallow North Caspian freezes over. The Middle Caspian transitions from the 4-5 meters (20 feet) depth of the North to about 190 meters (620 feet) before it reaches the South Caspian, where depths plunge to about 1,000 meters (3,300 feet).

Life in the north has adapted to harsh winter temperatures and the thick layer of ice that forms by January and stays until March. While commercial fishery, shipping, and oil production continues in the open-water regions, it’s here, in the frozen North, where seals come to raise their pups on the winter’s ice.

The Caspian seal is the smallest of the eared seals and the only marine mammal found in the Caspian Sea. It has listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) since 2008. In the 1930s, the seals were so numerous that many thousands were harvested each year, primarily for blubber and for the soft white fur of the pups. The current exact population is unknown, but best estimates are that about 70,000 remain. While active hunting has stopped, the seal population is still gravely at risk from many dangers, including fishing operations, diseases such as highly-fatal canine distemper, invasive jellyfish, and pollution. On December 5, approximately 2,500 dead Caspian seals washed up on the coastline of the Republic of Dagestan, Russia (located on the western coast and south of this image). The cause is being investigated, but authorities believe it to be “natural” and not from fishing or direct human activity.

Image Facts

Satellite:

Terra

Date Acquired: 12/16/2022

Resolutions:

1km (167 KB), 500m (469.5 KB), 250m (285.1 KB)

Bands Used: 1,4,3

Image Credit:

MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC

Tweet

On December 16, 2022, winter ice-up of the North Caspian Sea was nearly completed, thanks to rapidly falling temperatures in the closing days of autumn.

This pair of true-color images captured by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on board NASA’s Terra satellite only fifteen days apart illustrates the fast-forming ice. The upper image, acquired on December 16, reveals the entire area almost entirely ice-covered, with only small windows of open water visible. The lower image, acquired on December 1, shows only a thin layer of ice floating near the white mineral-encrusted shoreline.

The Caspian Sea, with a total surface area spanning about 143,200 square miles (371,000 square kilometers), is considered to be Earth’s largest inland water body. There are three distinct sections of the Caspian Sea, and, despite cold, harsh winter temperatures across much of the region, only the extremely shallow North Caspian freezes over. The Middle Caspian transitions from the 4-5 meters (20 feet) depth of the North to about 190 meters (620 feet) before it reaches the South Caspian, where depths plunge to about 1,000 meters (3,300 feet).

Life in the north has adapted to harsh winter temperatures and the thick layer of ice that forms by January and stays until March. While commercial fishery, shipping, and oil production continues in the open-water regions, it’s here, in the frozen North, where seals come to raise their pups on the winter’s ice.

The Caspian seal is the smallest of the eared seals and the only marine mammal found in the Caspian Sea. It has listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) since 2008. In the 1930s, the seals were so numerous that many thousands were harvested each year, primarily for blubber and for the soft white fur of the pups. The current exact population is unknown, but best estimates are that about 70,000 remain. While active hunting has stopped, the seal population is still gravely at risk from many dangers, including fishing operations, diseases such as highly-fatal canine distemper, invasive jellyfish, and pollution. On December 5, approximately 2,500 dead Caspian seals washed up on the coastline of the Republic of Dagestan, Russia (located on the western coast and south of this image). The cause is being investigated, but authorities believe it to be “natural” and not from fishing or direct human activity.

Image Facts

Satellite:

Terra

Date Acquired: 12/16/2022

Resolutions:

1km (167 KB), 500m (469.5 KB), 250m (285.1 KB)

Bands Used: 1,4,3

Image Credit:

MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC